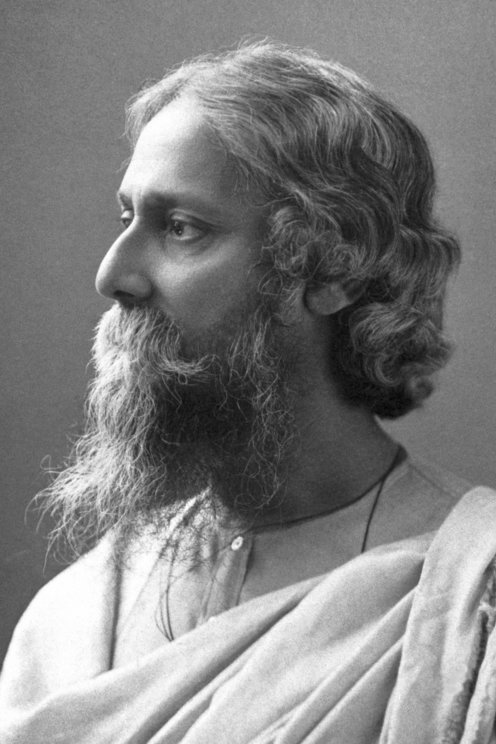

The dearly beloved poet of Bengal, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), stood at a particular juncture in time when the movement of ideas, peoples, faiths and cultures became that much more intertwined. As the world picked up pace, the smaller space–both physical and mental–in between people was prone to volatile and violent outbursts. Yet, where some built barriers, others built bridges; when nations claimed sole superiority and sovereignty over land, lives, and the globe–a voice in Bengal sang of yoga, of union, and of the universal religion of man.

Tagore’s works encapsulate, in essence, an integrated world. His poems express a union of both external exploration and internal insights. His songs revel in the delightful dance between the ineffable infinite and the fullness of the finite. His novels, plays, and other writings shed light on a life caught in motion–one constantly moving in between the vicissitudes of fate, embracing change while forever in pursuit of the perfection of truth. For Tagore, in a world on the brink of disunity, unity was to be achieved not by the identification with that which is transient, such as the nation or state, but that which is eternal through a process of creative meditation on the sublime–of achieving one’s spontaneous self-realisation.

‘Man has his other dwelling place in the realm of inner realisation, in the element of an immaterial value. This is a world where from the subterranean soil of his mind his consciousness often, like a seed, unexpectedly sends up sprouts into the heart of a luminous freedom, and the individual is made to realise his truth in the universal Man.’

- The Religion of ManTagore, 1930

By far, Gitanjali is Tagore’s best known work in the West. With this collection of 103 poems, he was the first non-European to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. In the preface to the collection, W.B. Yeats remarks that in Gitanjali ‘a whole people, a whole civilisation, immeasurably strange to us, seems to have been taken up into this imagination; and yet we are not moved because of its strangeness, but because we have met our own image’. Truly, a universal seeking seems to resonate from within the words that are heard in his ‘song offerings’. These words aim to frame and maintain the sublime self–of the all-pervading divinity and no-one else. This trajectory can be assessed with three striking poems picked from the beginning, middle, and end of Gitanjali.

First, there is desire; the fire that lifts one closer to, or further from, the self:

14. My desires are many and my cry is pitiful, but ever didst thou save me by hard refusals; and this strong mercy has been wrought into my life through and through.

Day by day thou art making me worthy of the simple, great gifts that thou gavest to me unasked–this sky and the light, this body and the life and the mind–saving me from perils of overmuch desire.

There are times when I languidly linger and times when I awaken and hurry in search of my goal; but cruelly thou hidest thyself from before me.

Day by day thou art making me worthy of thy full acceptance by refus- ing me ever and anon, saving me from perils of weak, uncertain desire.

Then about a little over the halfway mark, the Bengali poet pivots from the external to the internal, singing of seeking, seeing, and the inner being:

66. She who ever had remained in the depth of my being, in the twilight of gleams and of glimpses; she who never opened her veils in the morning light, will be my last gift to thee, my God, folded in my final song.

Words have wooed yet failed to win her; persuasion has stretched to her its eager arms in vain.

I have roamed from country to country keeping her in the core of my heart, and around her have risen and fallen the growth and decay of my life. Over my thoughts and actions, my slumbers and dreams, she reigned yet dwelled alone and apart.

Many a man knocked at my door and asked for her and turned away in despair.

There was none in the world who ever saw her face to face, and she remained in her loneliness waiting for thy recognition.

Finally, there is completion, synthesis, and realisation:

95. I was not aware of the moment when I first crossed the threshold of this life. What was the power that made me open out into this vast mystery like a bud in the forest at midnight!

When in the morning I looked upon the light I felt in a moment that I was no stranger in this world, that the in- scrutable without name and form had taken me in its arms in the form of my own mother.

Even so, in death the same unknown will appear as ever known to me. And because I love this life, I know I shall love death as well.

This child cries out when from the right breast the mother takes it away, in the very next moment to find in the left one its consolation.

The divine feminine, the Mother, envelops and nourishes him to bring forth the light within. By her grace, he stands face to face between the finite and the infinite–with that which is true, unique, and intimate. Now, more than ever, Tagore’s journey lights the way of the same universal journey we must all undertake to see the dawn of a new day. In a world steeped in disunity, following in his footsteps, listening to his melody, will help us see and bring us closer to unity. In essence, to bridge the gap between you and me.